When conversations turn to wellbeing, they often drift into the personal. Resilience. Self-care. Better boundaries. While these matter, they can also obscure a more uncomfortable truth.

Persistent stress and burnout are rarely individual failings. They are signals that a system is not working as designed.

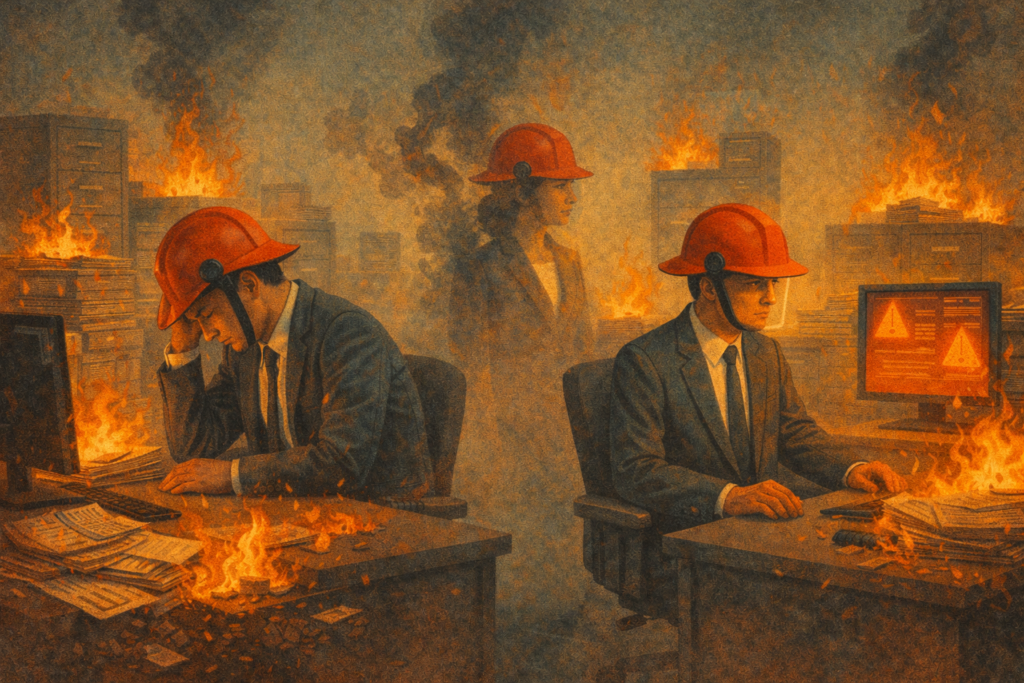

Firefighting extracts its cost from people

In a firefighting culture, pressure does not vanish. It is redistributed.

Deadlines are still met, but through longer hours. Gaps in processes are bridged by memory and experience. Errors are caught late because someone stayed alert just long enough to spot them.

This kind of effort feels manageable in the short term. Over time, it becomes exhausting.

People stop having space to think. They stop learning. They stop feeling proud of their work. Eventually, they stop believing that things can improve.

Burnout is not sudden

Burnout is often described as a cliff edge. In reality, it is erosion.

It shows up first as irritability, fatigue, or disengagement. Then as increased sickness absence, reduced confidence, or mistakes that would not previously have happened. By the time someone leaves, the conditions that caused it have usually been in place for years.

Organisations are often surprised by departures that felt inevitable to the people experiencing them.

Why wellbeing is a leading indicator

Wellbeing is often treated as a downstream outcome. Something to address after performance dips.

In reality, it is an early warning system.

When people are constantly stretched, it signals that demand consistently exceeds capacity. When teams rely on heroics, it signals that processes are brittle. When stress becomes normalised, it signals that the system has no margin.

Ignoring these signals does not make them go away. It just delays the consequences.

The limits of individual fixes

Wellbeing initiatives that focus only on individuals can inadvertently reinforce the problem.

Mindfulness sessions do not create capacity. Time management training does not remove overload. Encouraging people to take breaks does not help if the work simply piles up in their absence.

Without addressing system design, these interventions ask people to cope better with conditions that remain unchanged.

Designing for people, not endurance

Healthy systems assume people are human.

They include space for thinking, learning, and recovery. They allow work to slow down without everything breaking. They reduce reliance on individual effort by improving processes and expectations.

This is not about lowering standards. It is about creating conditions where high standards are sustainable.

If firefighting is constant, wellbeing will always be fragile. Extra capacity is not just a productivity issue. It is a human one.

In the final article, I will look outward and draw lessons from other sectors that have long understood the value of buffers, redundancy, and margin, and why future-ready organisations plan for slack rather than hoping they can cope without it.